-

- SHIMANO Trail Born Expands Mountain Bike Trails Worldwide

- Discover how SHIMANO Trail Born is supporting trails and riding communities worldwide with 21 new projects launching in 2026.

- 18/02/2026

SELECT LOCATION AND LANGUAGES

GLOBAL

AMERICAS

-

BELGIUM

FRANÇAIS

-

BELGIUM

NEDERLANDS

-

NETHERLANDS

NEDERLANDS

-

SWITZERLAND

DEUTSCH

-

SWITZERLAND

FRANÇAIS

-

SWITZERLAND

ITALIANO

-

AUSTRIA

DEUTSCH

-

FRANCE

FRANÇAIS

-

GERMANY

DEUTSCH

-

ITALY

ITALIANO

-

SPAIN

ESPAÑOL

-

PORTUGAL

PORTUGUÊS

-

POLAND

POLSKI

-

UNITED KINGDOM

ENGLISH

-

SWEDEN

SVENSKA

-

DENMARK

DANSK

-

NORWAY

NORSK

-

FINLAND

SUOMI

EUROPE

ASIA

OCEANIA

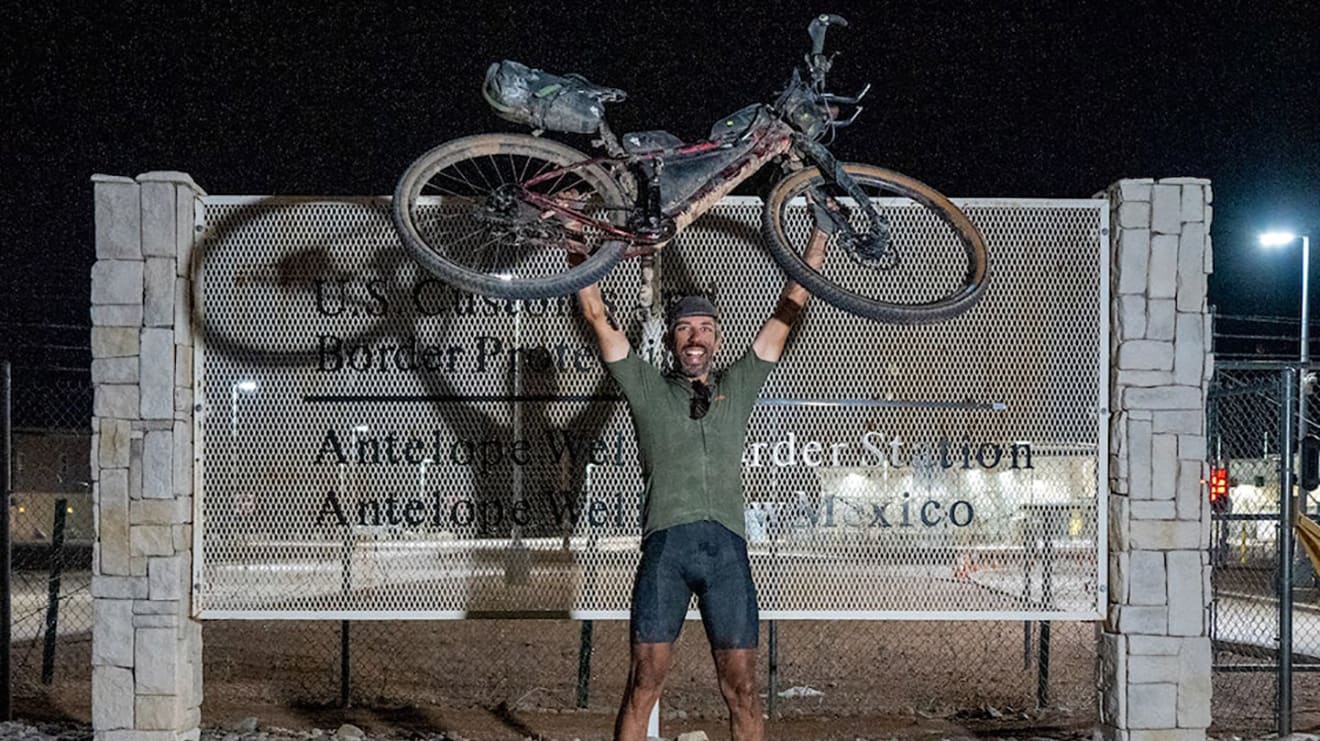

For fans of gravel bikepacking, Sofiane Sehili probably doesn’t need any introduction. His palmarès contains victories in the world’s biggest and toughest bikepacking events. We met up with him in his home city of Paris after his recent success in the 4,400 km (2, 275mile) Tour Divide event and chatted about eight-hour hike-a-bikes, block headwinds and what the future holds for him.

“I rode for nearly 40 hours and then stopped for a 15-minute nap at the side of the road. After the nap I felt OK, and I was good to continue riding through the night. That was enough sleep,” says Sofiane with a deadpan expression on his face. It is perfectly normal to him, but it’s part of what makes him such an incredibly successful ultra-endurance athlete. As a regular gravel rider or bikepacker, it’s easy to assume that success in multi-day races comes down to outright speed, technical skills or mind-blowing levels of stamina – and to a certain extent, this is all true. But in Sofiane’s case, his superpower appears to be all the above plus the ability to function on volumes of sleep so miniscule that lesser mortals would turn into a gibbering wreck if we tried to replicate it.

Sofiane’s game plan for the Tour Divide, which runs from Banff, Canada to New Mexico, was simple – avoid unnecessary stops to resupply. He figured that the majority of his biggest competitors would stop at the first possible re-supply point at the 250km point in Fernie, British Colombia. “Everybody stops there, and when I last did the event back in 2019, I stopped there too, but I don’t think it was necessary. This time I thought to myself, if I have food left, why stop? I was with Manu [Cattrysse] and Josh [Ibbett] this time and I knew they would probably stop. When I bought my groceries before the race started, I was at the supermarket and at first I choose one sandwich and then another. And then I thought I may as well actually grab four because I’m going to eat them anyway. I wasn’t really even calculating – every time I bought something, I thought, well, I might as well grab two. I left with a big collapsible backpack absolutely full of food. I thought back to all the extra stops that I did back in 2019 and how unnecessary they’d been. If you pack properly there’s no need to stop more than once a day.”

“I knew I could ride more without sleep and if I didn’t stop it meant I could save USD $200.”

Despite being one of the world’s top ultra-endurance racers, sometimes mundane practical considerations dictate how his participation in an event evolves. “The second night of the event I was actually quite keen to stop. I’d ridden straight through the first night, but when I arrived in Colombia Falls I couldn’t find a hotel for less than USD $200 a night, so I decided to push on through the night instead. I knew I could ride more without sleep and it meant I could save dollars, so I might as well do it. I did initially try to find a church that was open, or sometimes Post Offices in the USA have sheltered porches where you can sleep for an hour, but everything was closed.”

Some of the biggest headlines from the 2022 Tour Divide were weather/climate related. Snowstorms. Howling gales. Torrential rain. Thunder and lighting. Forest fires. In short, sub-optimal conditions for riding 4,000 km across the United States . “The weather was pretty horrible for the whole event. The snow wasn’t actually the worst part; when you first get to the snow and have to get off and push your bike for 90–120 minutes, it gives some of your muscles a bit of a rest. Afterwards you’re eager to get back on your bike. You hit the first downhill, exhilarated and happy to be back riding. Whereas, imagine fighting a headwind for three straight days through Wyoming and Colorado – we had a block headwind at around 30 km/h, with gusts of around 50km/h. It was hell. Even when it stops or you get to somewhere sheltered from the wind, you’re just really tired from fighting that wind all the time."

“The worst of the weather predictions actually happened this year!”

Sofiane has an incredibly detailed memory of the race and as he sits opposite us in the late afternoon Parisian sunshine you can see him mentally review it scene by scene. “I wasn’t really aware of how the bad weather was going to get and how much snow there would be on top of the highest passes. I was just doing my own thing. You get people on event Facebook chat groups who try and make everyone else scared, often based on their own insecurities, but I try not to listen to them. I tried to remain optimistic, but it was not really a year to be optimistic – the worst of the weather predictions actually happened this year!” he says, smiling wrily. “I calculated that I spent seven hours of the first fifty hours of the race doing hike-a-bike over snow, plus another hour doing the same when I reached Wyoming,” he continued. “Some of the riders behind me had significantly worse conditions though – I heard that so much extra snow had fallen after I crossed the highest passes, that sections where I had to hike-a-bike for 2.5 or 3 hours were taking more than double for riders further down the field. That was the real benefit in me not stopping for the first forty hours of the race.”

“That’s the way that I stay motivated – I basically lie to myself.”

For an event as demanding as Tour Divide that takes over two weeks to complete, motivation is a vital part of the game. “I try and find small goals. I tell myself things like ‘it’ll get better after such-and-such a point, or after that next bit.’ You lure yourself into thinking that this bad patch can’t last that long and that things will get better further down the route. That’s the way that I stay motivated – I basically lie to myself. Ultimately, I’m there to win. The whole point is to do your absolute best. In bikepacking all the top-level racers hold ourselves to very high standards. The nature of the sport is so much about pushing yourself and pushing the limits and trying to find out what you can do, that when you’re not actually pushing your limits, you feel guilty for not trying harder. Even if I do well and I win an event, if I feel that I haven’t done my absolute best than afterwards I look back and I think OK, next time I need to find a way to be more efficient and to deal with situations better.“

“This section was very susceptible to flash flooding and when it gets wet it becomes almost impassable.”

With an event as long as the Tour Divide, participants are likely be affected by situations which are out of their control. During the 2022 event a huge forest fire in New Mexico in the run-up to the start meant the organisers needed to re-route participants away from the danger. “The section through New Mexico really took me by surprise.” Sofiane explains. “The new section of the route was much shorter [which is why the finishing times of riders in the 2022 event can’t be considered direct competition to the times set by riders in previously years]. Since the new route was shorter and had more paved sections, what the organisers did was to include one section which is in the Great Divide MTB route but not normally included in the Tour Divide event route. This section is nearly all on gravel, but it goes through an area which is very susceptible to flash flooding and when it gets wet it becomes almost impassable. At the time we set off, New Mexico was on fire and no-one expected that the monsoon would arrive early and that this was going to be problematic. But that’s exactly what happened. I missed some of the rain because I was ahead of it, but when I got to New Mexico it was already raining—but not yet monsoon rain. I ended up being the only rider that rode the full re-routed course that had been put in place for this year.”

The speed differential between Sofiane and his fellow competitors became most apparent during this section of the event “For the riders behind me, they arrived at this new gravel section as the full monsoon conditions set-in and it was hell. The first rider, Manu, called the organiser and told him what was happening and as the organiser knew how at risk that section was from flash floods, he re-routed everyone except me, as I had already passed by at that point. The water levels rose rapidly, and I had to do actual river crossings, which I wasn’t expecting. It took me thirteen hours to do a section of the event that on the normal route would have been 8 or 9 hours.”

“I was completely exposed in the middle of the open road and I was there like a sitting duck.”

After deep snow and block winds, the riders next had to face torrential rain and biblical storms. “Even when I got through the gravel section and back on the paved route, the rain was like something I’ve only ever seen in tropical countries – it was bouncing off the road. The road was completely flooded and there were rivers of muddy water flowing down from the surrounding hills. In places the water on the road was hub depth. The local people are used to it, but a couple of them stopped their vehicles as they passed by me to make sure I was OK. One guy in a camper stopped and warned me about how bad the weather was that was coming up behind me. The sky behind me was completely black and there were lightning strikes pretty much every thirty seconds all around me. There were no trees, I was completely exposed in the middle of the open road and I was there like a sitting duck. I’ve been in some pretty difficult situations before on my bike, but this was one of the scariest because I had no choice but to keep going.“

“I found a campground nearby and I sheltered in the toilet for 6 hours, wrapped in an emergency blanket.”

The last-minute nature of the re-routed section meant a lot of the riders, including Sofiane didn’t have as much detailed information as they would have liked. “When I was doing the pre-event research, I knew that from the top of last pass, the next section was marked as no-service. As the pass was so high and it was raining so hard, I was worried about getting hypothermia and that was one of the reasons I stopped and sheltered in the campground toilet. This was all the re-routed section of the course, so no-one knew it really well. It turns out there is a ‘trail angel’ towards the bottom of the descent and you can stay on her porch which is sheltered from the weather. She puts a sleeping bag and snacks there for racers. If I had known that in advance, I would have probably just bombed down the descent and then spent an hour in that sleeping bag and then kept going. From that point onwards the altitude is only around 1500m so even if the temperature had remained low, I would have been ok. None of the racers knew about this trail angel, but she posted on the Facebook group for the event to say ‘Hi, I’m here, this is what I offer.’ Unfortunately for me it was too late as I’d finished the race already by the time she posted.”

Although Sofiane’s unscheduled stop allowed him to get some rest, it caused some other issues instead: “When I did my pre-race research, I knew that during this section, which is around 300kms in length, there is no chance at all to re-supply with food, so you basically have to be self-sufficient. I’d planned for this, so I was carrying a ton of food, which meant I didn’t need to stop. I hadn’t budgeted for the six hours that I sheltered in the campground toilet though, so I ran out of food for the last 60 or 70kms into Silvercity, meaning I had to go off-route to find food, so that was another hour lost, but at this point eating was more important than saving an hour of time.”

“I wanted to win it in the fastest possible time, ideally under fourteen days. That was my goal when I started the race.”

Not only did Sofiane want to win the event, he also wanted to set the fastest time. Mike Hall’s course record has stood since 2016 and is an incredible 13 days, 22 hours and 51 minutes. Sofiane initially wanted to try and beat this, but the course alteration meant this was unlikely to be possible. “We knew right from the start that the course was going to be re-routed, so it wasn’t going to be the record course and my finishing time wouldn’t be directly comparable with Mike Hall’s record. Obviously, I was disappointed, as I wanted to give it a shot. I had a vague hope that the section in New Mexico that was closed due to forest fire might re-open before I reached it. The organiser told me if this happened, they would re-route the racers onto the original route, which meant the record time was definitely a possibility. Sadly, the fire damaged section didn’t open until the day I finished and all the riders did the re-routed version.”

“My time this year was the fifth fastest in history, despite the conditions and that gives me a lot of confidence.”

“As soon as I knew that I wasn’t going to be able to get to challenge Mike’s record, I just focussed on winning the event. But having said that, I wanted to still make a statement with my winning time. My goal was thirteen and a half days, but given the 8 hours of hike-a-bike in the snow I knew pretty early on that it would be super hard. Anyone who finishes this event in these conditions has made a hell of an achievement. I was disappointed that I didn’t get to challenge for the record, but I was happy that I won one of the toughest editions of the Tour Divide ever. The conditions this time were significantly harder than in 2016 when Mike set the record – he did an amazing job and he was tremendously fast – but I was there that year, and the conditions were perfect from start to finish.“

Every multi-day event comes with ups and downs, but Sofiane’s eyes light up when he recalls some of the sights along the Tour Divide: “For the first four or five days I was so focussed on racing and being as fast and efficient as possible and making sure that my competition was as far behind as possible, I didn’t really allow myself the time to appreciate anything that was around me. At the top of a hike-a-bike section there was a glacial lake on one side and pine forest on the other and everything was covered in snow, but it was not an option for me to contemplate it. The scenery was much less important that what I was actually doing. I couldn’t find the necessary mental space to feel any sort of emotion about where I was riding. Eventually something changed once I knew I had a significant gap. Here’s when I opened myself up to all of the emotions – both the good and the bad. In Montana I started riding around 2am, after a 90-minute stop. At around 9am I was in a valley, in a place that I hadn’t remembered from previous attempts, so it was quite unexpected. I had a tailwind and everything was going well and it was the first time during the race that I let myself be outside of the race and just in the ride. For a short while I was no longer racing, just riding, and I was able to observe the scenery and appreciate how lucky I was to be there.”

“It’s apparently miserable and super hard, but also so beautiful.”

Before letting Sofiane go back to his daily life in Paris, we had one more obvious question for him – what was next on his bucket list? Was there anything left out there big enough to challenge him? “There aren’t many other big events that are still to be won, but it’s a very young sport and new events keep popping up. I’ve won enough big races to cement my legacy and establish myself as one of the top racers, which means I can go to different events with different motivation. I’ve been considering the HighlandTrail550 for a long time. Every year I dot-watch it and think how horrible it looks, but I so badly want to do it and I don’t know why! It’s apparently miserable and super hard, but also so beautiful. It’s quite a mythical race for the hardcore bikepacking community. I’m not sure I have the mountain bike skills to win it, but I’d like to try it. It normally takes the winner a couple of attempts to succeed. I’ll be OK this time around if I can just finish it.”

“Even if I reach the point where I can’t find big goals to challenge myself with, I want to stay involved in the sport.”

And what about his life after racing? “I’m forty now, so it’s not like I can stay on top of my game for another ten years, but I’ll always make sure that I have fun on my bike and enjoy my racing. At the minute, I still really enjoy being out there, spending way too much time on the bike and being tired all the time. I still love winning and perhaps more importantly, I love the feeling of camaraderie at the end of an event, with everyone sitting at the finish exchanging stories. I’m really happy to be a part of this community and I aspire to keep being a part of it – not just as someone who wins races but as someone who stands up for the values of the sport. I love the fact that the community respects my opinion. All of the top racers that I’ve met, as well as having strong bodies, are smart and articulate and have strong values and that’s why I love being part of this community. I’d love to become an event organiser at some point and keep giving back. I don’t know exactly what shape it will take, but I want to stay involved and fight for the values that are at the core of this community.”

.jpg)