SELECT LOCATION AND LANGUAGE

GLOBAL

AMERICAS

-

BELGIUM

FRANÇAIS

-

BELGIUM

NEDERLANDS

-

NETHERLANDS

NEDERLANDS

-

SWITZERLAND

DEUTSCH

-

SWITZERLAND

FRANÇAIS

-

SWITZERLAND

ITALIANO

-

AUSTRIA

DEUTSCH

-

FRANCE

FRANÇAIS

-

GERMANY

DEUTSCH

-

ITALY

ITALIANO

-

SPAIN

ESPAÑOL

-

PORTUGAL

PORTUGUÊS

-

POLAND

POLSKI

-

UNITED KINGDOM

ENGLISH

-

SWEDEN

SVENSKA

-

DENMARK

DANSK

-

NORWAY

NORSK

-

FINLAND

SUOMI

EUROPE

ASIA

OCEANIA

- Découvrez Pi Manson et Ted James, deux cadreurs indépendants qui racontent comment ils ont conçu un vélo sur mesure autour d’un groupe unique.

- Découvrez tout ce qui est nécessaire, du début à la fin, pour monter un vélo destiné au BESPOKED, le salon où des cadreurs indépendants présentent leurs montages sur mesure.

- Découvrez le CUES Polished Silver, présenté dans toute sa splendeur, monté sur deux cadres uniques.

CUES " Polished Silver"

Nous avons lancé cet été l’édition Polished Silver de notre SHIMANO CUES, en référence directe à nos origines dans la métallurgie et la forge. Le look classique associé à la robustesse qui caractérise notre gamme CUES, avec une finition unique qui mérite un montage unique.

Ou deux.

Voici Ted et Pi.

Un groupe, deux montages.

Nous nous sommes donné pour mission de dénicher deux artisans constructeurs de cadres indépendants capables de retranscrire l’esprit du CUES Polished Silver dans une réalisation sublime, juste à temps pour le salon BESPOKED de Dresde. Ted James et Pi Manson nous avaient été chaudement recommandés, et après quelques recherches, nous avons compris pourquoi.

Dans l’univers du cyclisme, les constructeurs de cadres indépendants se situent au carrefour du geste de l’artiste et du regard du mécanicien : chaque vélo devient alors une célébration unique de ce plaisir simple et universel que le monde entier partage : rouler à vélo. Et nulle part ailleurs cette joie ne s’exprime mieux qu’au BESPOKED, le plus grand salon européen du vélo artisanal.

Nous avons confié à Ted et Pi leur mission :

Traduire l'esprit du CUES Polished Silver en une magnifique réalisation juste à temps pour le salon BESPOKED de Dresde.

Ils l'ont acceptée. Ils ont fait un montage. Et ils l'ont réussi.

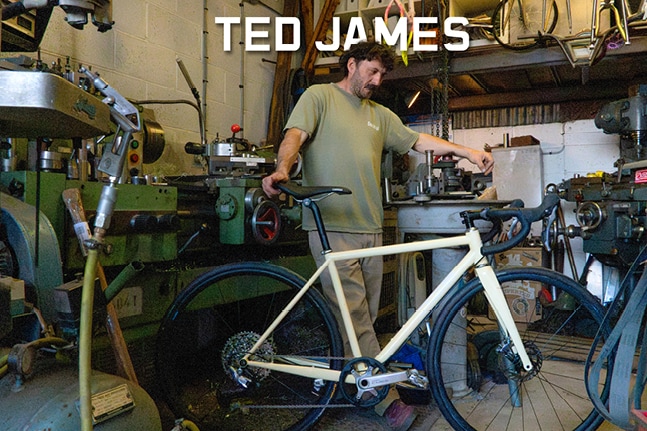

Ted James Design

Comment avez-vous procédé pour élaborer le concept de votre montage ?

Premièrement je me suis demandé "comment bien mettre en avant ce groupe?!" J'ai senti que je devais choisir quelque chose qui ne serait pas trop extravagant. Un simple cadre en acier, qui ne fait pas trop coursier, sans prétention ultra-performante, mais un vrai bon vélo de route à l’ancienne – un vélo traditionnel équipé d’une transmission moderne, avec de grands écarts de développement et en mono-plateau. Un vélo sur lequel vous pouvez rouler toute la journée.

J'ai choisi de l'acier Columbus pour le cadre. Puis j'ai trouvé la géométrie adéquate. Pas pour des performances élevées, mais pour du confort, vous voyez ? Pour la couleur, je voulais quelque chose de sobre. Un look classique avec une petite touche rétro. Fourche avec feutrage carbone adapté. Pneus en 32 mm. Le reste de la géométrie s’est ensuite imposé de manière évidente, en suivant la fourche.

Classique, oui, avec un peu plus de confort.

Et concrètement, comment passe-t-on du concept à un vélo fini et prêt pour le BESPOKED ?

Je fabrique moi-même beaucoup de composants. J’ai usiné le tube de direction, le pontet de frein, et j’ai acheté le boîtier de pédalier ; au final, la soudure, c’est la partie la plus rapide de la fabrication. Ensuite, il y a la peinture, que je réalise également moi-même. Je cherchais quelque chose qui s'accorderait bien avec l'argenté et qui soit un peu différent des vélos qu'on voit dans les magasins. Donc, un jaune clair avec un effet d'éclaboussures très léger, rappelant beaucoup de peintures de VTT des années 90 — il y a là un équilibre à trouver pour conserver le look classique tout en y ajoutant une touche d'originalité.

Quelques jours de préparation, d'usinage et de découpe des tubes ; une autre journée de soudure ; les finitions ; puis la peinture qui prend quelques heures. Trois passes d’apprêt, trois couches de teinte principale, un effet « paint flick », puis trois couches de vernis transparent. Ça représente une semaine de travail du début à la fin.

Parlez-nous un peu de vous.

J'ai créé cette entreprise en 2010. Mais j’avais déjà deux ans de fabrication de cadres derrière moi. Au départ, je faisais surtout de la réparation. Depuis, je m'y consacre à plein temps, en fabricant des vélos de route, des gravel de randonnée, des BMX et des VTT. Je fais moi-même du BMX. J'ai toujours rêvé de fabriquer un BMX. C’est ce qui m’a lancé. Certains vélos sur lesquels j'ai roulé se sont cassés, alors j'ai cherché à en fabriquer un qui serait plus solide. J'ai ensuite reçu des demandes, pour des enfants de quatre ans mais aussi pour des coureurs professionnels. Depuis les roues de 16 pouces jusqu'aux BMX en titane. Je travaille l'acier et le titane.

Du coup, la grande question : l’acier, c’est réel ?

L'acier est un très bon matériau pour la fabrication de vélos. On peut avoir des tubes assez fins avec une rigidité suffisante, alors que le carbone nécessite une plus grande largeur des bases pour atteindre la même rigidité. L'acier offre une certaine souplesse verticale, ce qui procure une sensation de confort accrue. L’acier a de la souplesse, ça apporte du confort. Sur pas mal de vélos industriels, cette souplesse disparaît complètement.

Pi Manson / Clandestine

Comment avez-vous procédé pour élaborer le concept de votre montage ?

J'avais en tête de fabriquer un vélo qui convient à tout le monde. L’important, c’est de prendre du plaisir. En général, je conçois des vélos pour des personnes dont la priorité n’est pas forcément la vitesse. Le plaisir, la sécurité et le confort comptent davantage. D’où l’importance de l’éclairage et des fixations pour porte-bagages/ J'ai d’ailleurs fabriqué un porte-bagages qui évoque bien cet usage.

En termes de géométrie, je voulais privilégier le confort et la stabilité plutôt que la vitesse. Il a donc un avant du vélo plus haut, un tube de direction relativement long et une fourche longue, ce qui permet de relever l’avant du vélo, de positionner plus haut le bas du cintre et de le rendre plus facile à atteindre pour le cycliste. Il est primordial de pouvoir utiliser facilement la partie basse du guidon lorsqu'on roule sur un vélo de gravel. L’essentiel, c’est que quelqu’un puisse, en pratique, rester en bas du cintre toute la journée. Et les cocottes sont vraiment redressées : on peut adopter une position redressée pour profiter de la vue, plutôt que ce que ce soit la position par défaut — grâce à un angle de direction ouvert. Les bases arrière sont aussi relativement longues — 450 mm, pas comme sur un vélo de gravel ultra-compact et racé. Cette longueur contribue à stabiliser le vélo. Associée à un tube supérieur long et à une potence courte, elle permet d'obtenir un empattement long. Cela favorise la stabilité, et rend le vélo moins nerveux et plus confortable à piloter en tout-terrain.

Je fabrique aussi moi-même mes fourches en acier, ce qui m’évite d’être limité par les options existantes. Ça me permet également de donner du cintrage aux fourreaux de fourche pour obtenir un look classique. En général, je veux que mes vélos aient un style classique. Je puise mon inspiration dans l’histoire du cyclisme, jusqu’aux « safety bicycles » : les fourches étaient cintrées, avec un cadre à double losange. Je souhaite conserver un lien avec cette tradition cycliste ; je ne veux pas qu'elle se perde. J’ai le sentiment de faire partie d’une lignée informelle de cadreurs ; c’est quelque chose de vraiment beau. Je pense vraiment que cela mérite d'être préservé.

Et concrètement, comment passe-t-on du concept à un vélo fini et prêt pour le BESPOKED ?

Je commence avec une boîte de tubes. Je prends toutes les mesures nécessaires pour m’assurer qu’il n’y aura aucun problème à la fabrication. Ensuite, je vérifie que chaque tube s’ajuste parfaitement avec le suivant. J’utilise pour ça une fraiseuse et une machine à ébavurer les tubes abrasifs. C’est comme ça que tous les tubes sont coupés. Je fais encore l’ajustage des haubans à la main, par exemple, c’est presque plus rapide. Ils sont ensuite assemblés dans un gabarit. J’ai fabriqué le mien moi-même : il garantit le respect de la géométrie du vélo. Ensuite, tout est pointé dans le gabarit. On brase juste ce qu’il faut pour que l’ensemble tienne. Puis on passe à une brasure complète.

En général, je laisse mes clients choisir la couleur. Dans ce cas, le choix a été assez simple : la teinte était un peu plus classique. Elle rend bien en photo. Je fais poudrer mes cadres à la fin, quand tout est assemblé.

Parlez-nous un peu de vous.

J'ai lancé Clandestine en 2017 dans le Devon, à l'extrême sud-ouest du Royaume-Uni. Juste à la lisière du parc national de Dartmoor. J'étais à Bristol avant ça. À Bristol, il y avait une communauté cycliste incroyable. C'était très facile de se familiariser avec tout le milieu cycliste là bas. J'ai rencontré d'autres personnes qui s'intéressaient à la fabrication de cadres. J'ai donc commencé par fabriquer des porte-bagages pour moi et mes amis. Ensuite, pour les amis de mes amis. Puis pour les amis des amis de nos amis. Les porte-bagages m'ont vraiment permis de me lancer. Je me suis penché sur différentes manières de transporter du matériel sur les vélos.

Équiper son vélo de porte-bagages vraiment aboutis transforme totalement la pratique. Celui monté sur le vélo Shimano est extrêmement rigide, très léger et dispose d’un passage de dynamo intégré : c’est d’une grande élégance. On peut se montrer créatif avec les porte-bagages si l’envie nous prend.

Donc, cette question de l'acier…

J’ai choisi l’acier parce que c’est l’âme et l’histoire du vélo. Dans la communauté où j’ai commencé tout ça, tout le monde bossait l’acier. Au Royaume-Uni, l'acier est très accessible. On apprend énormément des autres artisans. L’acier, c’est hyper tolérant à travailler. Ils font des ressorts avec. Ça veut tout dire pour moi. Ultra résistant, mais souple. Hyper sécurisant. Bonne durée de vie en fatigue.

Et c'est tout simplement élégant, vous voyez ?